Dr. Myles Mac Evilly.

As early as April 1918 the newly appointed Lord Lieutenant and Military Commissioner in Ireland, Lord French, in a letter to Prime Minister Lloyd George during the Conscription Crisis, advocated the use of airpower, “ that ought to put the fear of God into those playful young Sinn Feiners 1 ( 1 ) ,notwithstanding that military operations by Irish Republicans had not by then even begun. Lacking, he thought, enough troops on the ground he recommended the establishment of strongly entrenched ‘ Air Camps ‘, one in each province in Ireland out of which military aircraft could “play about” with either bombs or machine-guns “ if the locals got out of hand“. However, permission to attach machine-guns to operational aeroplanes in Ireland was not given by Lloyd George until the end of March 1921 (2) on the grounds that their use could be deemed potentially indiscriminate and disproportionate, thus relegating the R.F.C./R.A.F. in the intervening period to a primarily air transport, communications and reconnaissance role in support of the British Army whose complement in Ireland had increased from 53,000 troops in May 1919 to 83,000 by July 1921 (2b). In effect, the British Army’s role was considered a ‘ policing ‘ one on behalf of the civil powers . Military support against the burgeoning Irish Republican movement was provided to the RIC throughout this period by the British Army, to which the R.F.C./R.A.F. provided air support also.

By March 1921, however, with a deteriorating security situation and under pressure from Churchill and Bonham Carter ( Officer Commanding R.A.F. Ireland ) together with the Chief of the General Staff, General Macready, the R.A.F. now had political permission to become more aggressive against the I.R.A. (3). Co-operation between the British Army /RIC and the R.A.F. was by then better integrated by having a R.A.F. liaison officer embedded in each Brigade headquarters for advice on reconnaissance duties (4), while air to ground communication technology and aerial photography were improving.

The degree to which the R.F.C./R.A.F. contributed to the overall British military effort in Ireland during the War of Independence has been questioned in the past (5) but recently a more favourable analysis of their role, primarily in the South , has been made (6) . This article attempts to assess whether RAF air power had a similarly influential role on the activities of the I.R.A. in West Mayo, bearing in mind that the West Mayo Brigade did not become a functionally active unit until late in the War of Independence and only then with the formation of the Flying Column in March 1921.

Organisation and Deployment.

By May 1917 various airfield sites in Ireland were selected by the Lands Officer at Irish Command H.Q. ( Army ) to facilitate the training of new pilots for the expanding R.F.C. These sites were confirmed by Major Sholto Douglas O.C. 84 Squadron and later Marshall of the R.A.F. Air Staff, while on recuperation leave in Ireland after crashing into a plough – horse on taking off in Triezennes in Northern France. His father, Professor Robert Langton Douglas , was Director of The National Gallery of Ireland in Dublin, at the time. In his autobiography ‘ Years of Combat‘ ( Collins, London, 1963 ) Major Douglas recalls landing his aeroplane in the Phoenix Park close to the present day Arus an Uactharan, on his arrival in Dublin!

In November 1917 five substantial Training Depot Stations ( TDS ) were built in Ireland, at Baldonnel ( No. 23 TDS), closed 1922, and Tallaght (No. 25 TDS ) in West Dublin , Gormanstown (No.22 TDS) in North Dublin ( compulsorily purchased from 4 local families! ) Aldergrove outside Belfast, Collinstown in North Dublin ( No. 24 TDS ), as well as the Curragh (19 TDS ) in Kildare which already had a landing field since 1913 and which was also the seat of British Military power in Ireland. In 1915 an aerodrome had been commissioned near the Curragh Camp for the R.F.C. which was, at that time, a Corps of the Army. By Dec.1917 the 19th Training Squadron with a complement of 24 aircraft in canvas hangars and 328 support personnel was based there. Later in 1918 a new unit, The Irish Flying Instructors School, was founded there. These Training Depot Stations were uniform in design and were intended to be permanent structures that included administrative buildings, aeroplane hangars having six in each Station erected in three pairs, aeroplane maintenance areas, officers mess, stores, a wireless station and women’s (WRAF) quarters. In the time period of WW1 ( 1914-1918 ) a total of 23 airship and airfields were developed throughout the island of Ireland on behalf of the R.F.C./R.A.F. , R.N.A.S., and the US Naval Air Service. In addition, as many as 60 emergency landing sites were created in the countryside on the grounds of the landed gentry , at or near a military or R.I.C. barracks and marked with a large cross. The different aviation schools then in Ireland used training methods pioneered by Lieut-Colonel Robert Smith Barry, who had Irish ( Cork ) heritage.

In April 1918 both 106 and 105 Squadrons, each having RE8 biplanes , were selected to move to Ireland in support of the British Army in a ‘policing ‘ role and were fully operational by late May, in Fermoy ( 106 Sqdn.) and at Strathroy House outside Omagh ( 105 Sqdn.), in the latter case at the request of Lord French, in an antisubmarine role ostensibly but in reality for aerial reconnaissance of Nationalists activities with the Conscription Crisis approaching .( His militaristic policies later lead to his family home in Fermanagh being destroyed by the I.R. A. in April 1921 in a counter- reprisal, prior to his recall to London) This was the first deployment of military aircraft in Ireland since a flight by No. 2 Sqdn R.F.C. from Montrose, Scotland, commanded by Major Charles James Bourke and made up of 6 BE2’s and a Farman Leghorn aeroplane participated in joint Inter Divisional and Command Maneouvres with the British Army at Rathbane Camp, Co. Limerick in early September 1913, in the first overseas flight for the R.F.C.

Between January 1918 and October 1919 landing sites were newly developed at Ballylin House near Ferbane, Co. Offaly ( so-called ‘RAF Athlone‘ ), at Crinkill House near Birr 53 degrees 6 ‘ 00 N and 7 degrees 52’12’W (1919) on a 14 acre estate where detachments from 106 Squadron were deployed in Jan 1918 from Fermoy as part of the 11 ( Irish ) Group and including 141 Sqdn from March 1919 , and at Oranmore near Galway City , though not all airfields were operational at the same time. In August 1918 105 Squadron from Omagh had detachments at Castlebar ( C. Flight consisting of 6 RE8 biplanes commanded by Captn.W.U. Dykes ), at Oranmore ( A. and B. Flights under Major Joy ), at Collinstown, the Curragh, Baldonnel and Fermoy (7).In January 1919., because of flooding concerns on the local airfield , 106 Sqdn. ‘Detached flight‘ at Ferbane moved to Crinkill, Birr with a reduced complement of 8 officers and 55 men. Castlebar, Fermoy, Omagh and Oranmore were by now designated as 6th Brigade Stations, the 6th Brigade R.F.C. being responsible for Air Defence of the British Isles during WW1. By January 1919 both Squadrons were re-equipped with the new Bristol F2B Fighters to replace the older and slower RE8 aeroplanes.

No. 141 Squadron, newly equipped with Bristol F2B Fighter aeroplanes, was deployed in March 1919 from Biggin Hill in Kent to Tallaght Airfield near Dublin, with No’s 117 and 149 Squadrons arriving also at Tallaght later in the month, the latter squadron with DH6 aeroplanes serving in an an antisubmarine role over the sea approaches to Dublin Port , but arriving too late by 6 months to save the R.M.S. Leinster , torpedoed by U.B.-123 on October 10th 1918. Tallaght airfield closed in the 1920’s. By July 1919 the total complement of R.A.F. personnel in Ireland then amounted to 1789 officers and men . In August 1919 two Army cooperation squadrons each having a distinguished war-time background arrived in Ireland as part of a ‘Defence of Ireland Scheme‘ ( a comprehensive plan devised in October 1918 by the British Government for Ireland in anticipation of a German invasion or a generalised uprising ) resulting in the disbandment of 106 Squadron ( hitherto a training squadron ) on the 8th of October 1919 at Fermoy though some of their aircraft were deployed to 2 Squadron newly formed at Oranmore on 1st Feb.1920. Personnel and aircraft from 105 Squadron remained operational in a close air support role in Ireland until 1st Feb. 1920 when it also was disbanded, being reconfigured as 2 Squadron at Oranmore. 105 Squadron would later adapt an emerald coloured battle-axe onto it’s badge to commemorate the squadrons service in Ireland.

On arrival in Ireland in May 1918 the R.A.F. were legally accountable to the British Army on a day to day basis i.e.to the Competent Military Authority ( CMA ), a device the British Army used subsequently in other colonial ‘air policing‘ actions in Mesopotamia( Iraq ), The Transjordan, Somaliland against the Mad Mullah , and much later against the Mau Mau in Kenya in the 1950’s (8) . The armistice occurred in Nov. 1918 resulting in many skilled aviation personnel being demobbed or sent abroad . During the War of Independence seven flights from 2. Squadron and 100 Squadron ( flying Bristol Fighters in late 1920 ) were stationed at Castlebar, Baldonnel, Fermoy , Oranmore , Omagh and Aldergrove , all 6th Brigade Stations, the latter airfield having been especially constructed for the purpose of test -flying small numbers of the Handley Page V 1500 bombers amongst others, built by Harland and Wolfe between 1917 and 1920 . Also at Castlebar were 2 Sqdn. detached Flight from Baldonnel ( presently renamed Casement Airdrome ), from July 1920 to January 1921 under the command of Flight Commander ( and much later Air Commodore ) H. G. Bowen, and 100 Sqdrn commanded by James Leonard Neville Bennett -Baggs.

In 1918 the Oranmore Airfield was situated 5 miles East of Renmore Barracks, which was a Connaught Rangers Training and Parade Ground; it was 600 by 400 yards in dimension with a good surface and a slight slope to the South and East. It consisted of two aeroplane sheds, an officers mess, personnel quarters, an armoury, a hospital and a Wireless Shed. The Oranmore Airfield was involved in an aerial ‘drive‘ or search in the East Galway area after the killing of an R.I.C. inspector Captain Cecil Blake and a lady friend Eliza Williams together with two British Army officers, Captain. Cornwallis and Lieut. Mc Creery ( both from 17th Lancers ) at Ballyturin House near Gort on the 15th May 1921, as well as aerial reconnaissance after the Tourmakeady and Carrowkennedy ambushes.

Communication between the ground and aeroplanes were an issue that improved as the War of Independence continued. In April 1922, with the end of hostilities and with the risk of civil war looming, the Irish Flight of four Bristol Fighters commanded by Group Captain Bonham Carter were retained at Baldonnel to supervise the withdrawal of British ground forces from Ireland (9), escorting troop trains as they evacuated the British Army from the Curragh and Dundalk to Dublin Port, which had been delayed up to then following a petition by Collins to Macready to delay the evacuation in case the anti-Treaty group succeeded (9b), until 14th October 1922 when the Irish Flight ceased flying.

Aircraft and Equipment.

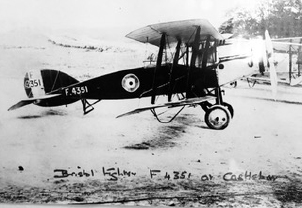

Following upon the South African General Jan Smuts report to the War Council in August 1917 the R.A.F. was formally established by the amalgamation of the Royal Flying Corps and the Royal Naval Air Service on the 1st April 1918. By December 1919 each squadron was equipped with the two-seater Bristol F2B Fighter biplanes, developed by Frank Barnwell in October 1916 and built by the British and Colonial Aeroplane Company Ltd, ( later The Bristol Aeroplane Company Ltd ), having had the RE8, an armed reconnaissance aircraft up to then. Ultimately these Bristol F2B Fighters saw service in No’s 100, 105, 106 and 141 Squadrons and the Irish Flight R.A.F. 1919-1921 operating out of Baldonnel, Castlebar, Tallaght and Collinstown airfields. They were armed with two machine-guns and were considered to be versatile fighters and ground attack aircraft, ( having a fixed, front-firing 0.303 in. ( 7.7 mm ) synchronised Vickers machine-gun for the pilot and a 0.303 Lewis gun to the rear in the observers cockpit attached to a Scarff Ring for mobility and having a range of 1,870 yards or 1.7km), though permission to use machine-guns on aircraft in Ireland was delayed until 24th March 1921. In a later version they had 275 h.p. Rolls Royce Falcon 111 engines, were capable of remaining airborne for two and a half hours flying at 125 mph and could carry up to 200kg of bombs. The wings, some of which were made in Carlow by the firm of Thomas Thompson, were covered in taut, lacquered ( with nitrocellulose! ), linen yarn from different linen mills in N. I., thus allowing Lord French to claim at the end of WW1 that “ the war was won on Ulster wings “!

Baldonnel became the H.Q. of the R.A.F. in Ireland in March 1920, the resident squadrons being No’s 2 and 100 Squadrons, each being the first RAF squadron dedicated to a formal Army co-operation role, supporting the sizeable British garrison in Ireland. Each squadron had three flights of four aircraft though by September 1920 there were only 18 serviceable aeroplanes available for active duty, for logistical reasons, primarily poor maintenance. Gormanstown airfield, built in 1917 as one of the early training depots began to be decommissioned as WW1 ended, and by January 1920 any aeroplanes that remained there were transferred to Baldonnel.

During the Mountjoy hunger strike of April 1920 clashes occurred between the British Army and supporters of the strike, leading to RAF aeroplanes flying as low as the eaves of houses in Phibsboro to intimidate the protestors (9c). Later that year on November 21st 1920 an RAF aeroplane was seen circling twice over Croke Park prior to the arrival of the R.I.C./Auxiliaries according to a report in next days ‘Irish Independent’ 22Nov. 1920. It was subsequently denied by the RAF that they had any connection with that days events ( Bloody Sunday ), that it was on another mission at the time and that its guns were not in fact operational!

Over the next six months and after high level intervention by Churchill and Sir Hugh Trenchard ( later to be the first Chief of the Air Staff ), No 2 Squadron was brought up to strength and deployed to Fermoy in the South where it was needed most (10). Also No. 100 Squadron there had their DH9 aeroplanes replaced by the more reliable Bristol Fighters. Fermoy airfield when developed for the R.F.C. in 1918 was then a long field, 300 by 400 yards, south of the old No 1 Cavalry H.Q. on the old Dublin Road on what was originally an old race-course and exercise- grounds for the British Army. An entanglement of barbed wire surrounded the Camp, interspersed by sandbag gun- emplacements and gates to allow access for the aeroplanes to the airfield .These were housed in three canvas hangars while RFC/RAF personnel lived in tents or primitive quarters made from aeroplane packing cases for two years when huts were provided. In Feb. 1922 the base was formally relinquished to Irish National Army forces ( known as the Brigade Headquarters Guards ) four days prior to the taking over of the Military Barracks in Fermoy.

The main duty of the R.F.C./ R.A.F. involved the dropping of mail and VIP passengers to military bases throughout Ireland as travelling by road was both time poor and dangerous, as well as providing aerial reconnaissance of roads and railways for sabotage as well as escorts to road convoys, the prevention of illegal drilling, dropping of British propaganda leaflets advising young men not to be ‘misled’, and searching for flying-columns post ambushes ( ‘drives ‘) and also aerial photography to identify static Irish Volunteer locations. Communication with the ground included the use of carrier pigeons ( as after Kilmeena/Skerdagh engagements ) and dropping message bags with coloured streamers to RIC outposts ( as sometimes occurred at the RIC barracks in Balla, Co. Mayo where a ring, 15 feet in diameter , of whitewashed stones, were laid in the garden to guide aeroplanes as they dropped messages and parcels intended for the ‘enemy’ (11). Other methods involved the use of Very lights and Klaxons as well as “T” Popham Signalling Panels ( developed 1917 ), a basic ground to air signalling system , prior to the advent of wireless telegraphy. An air to ground radio transmitter / receiver system was developed by the Marconi Company in early 1916 and was used by the R.F.C. in France and much later in Ireland as a CW ( Morse ) system, the Marconi Crystal Receiver on the ground receiving signals from aeroplanes, but not vice versa.

Castlebar Airfields.

A designated landing strip existed in Castlebar as early as September 1912 as one of the participants in the Irish Aero Club ( founded1909 ) sponsored Dublin-Belfast air race, James Valentine, went on to make exhibition flights afterwards in towns around Ireland , including Castlebar. Although an Airship Station at Castlebar was initially proposed by the R.A.F. this plan was altered later to an Advanced Aerodrome or forward landing ground for anti-Republican /IRA operations ( 12). This airfield was developed by the R.A.F. in Castlebar in May 1918 .By the 5th January 1920 it was still listed ‘as unavailable for civilian use‘. Prior to this, the R.F.C’s role along the East coast was primarily an anti-submarine one following upon the laying of mines off the Donegal coast in 1914 and the arrival of German submarines in the Irish Sea in January 1915. But after the entire coast of Gt. Britain and Ireland was designated as a ‘War Zone ‘ by Germany on 4th February 1915 different naval aviation sites throughout Ireland were chosen to counter this threat as in Bantry Bay, Ferrycarrig outside Wexford, Lough Foyle and Queenstown (for R.A.F. and U.S.N.A.V.A.S. ). In July 1918 a proposal was made by the RAF to develop permanent Seaplane Stations at Shannon Mouth, Gorteen Bay, Co. Galway and in Co. Mayo to oversee the West Coast of Ireland but this did not evolve as WW1 was coming to an end.

‘RAF Castlebar’, known locally as ‘ The Aerodrome Field‘, consisted of about 90 acres and was on grass. It was also known as the Drumconlan airfield, a 6th Brigade Station as recorded on Secret Ordinance Map 120, 16th Nov 1918. It lay 50 51 09 N and 009 16 41 W, north of the Castlebar to Breaffy road ( on the site of the present Baxter factory ) and 200 kilometres west-northwest of Dublin . In early January 1919 it was reported ( Connaught Telegraph Jan. 04 ) that Castlebar had been made a permanent centre for the Air Force ( sic ) and that the temporary aerodrome would shortly be replaced by a permanent structure, though no buildings or a hard surface were ever built .Between 1918-1921, as part of a thrice weekly mail service to Dublin from Castlebar, emergency landing strips were designated to include a field 3 miles east of Athlone and a private park near Carrick-on-Shannon, courtesy of the local gentry. A 2nd airfield that was developed later nearby, the Castlebar Airfield, at Knockrower 53 50 54N, 9 16 49W was south of the main Castlebar to Breaffy road and close to the Castlebar to Dublin Midland and Great Western railway line. This airfield later evolved into the Mayo Flying Club having a 600 yards tarmac strip until it’s closure in the 1960’s.

C Flight 105 Squadron RAF, Castlebar.

The Drumconlan airfield ( RAF Castlebar ) had wooden huts and canvas Bessenaux hangers, sited parallel to and 20 yards from the main road and sheltered by a wood of fir trees for protection from the prevailing winds. An apron of granite stones and loose chippings was laid down in front of the hangers by a local contractor. Later a runway of sorts was built but the surface was always soft. Fuel tanks there had a capacity of 4000 gallons of aviation fuel. Mains water was piped to the camp from the nearby town but there was no electricity. A workshop lorry engine at the airfield generated 110 volts DC of light after 10 pm at night(7ibid). Importantly for operational reasons , it also had a Wireless Station for air to ground communication ( as CW telegraphy ). Cadres from 105 Squadron continued in a close air support role ( to the Army ) at RAF Castlebar until Feb. 1920 with Bristol F2b Fighters while detached flight of 2 Squadron from Oranmore remained until July 1920 and D Flight of 100 Squadron from Baldonnel until January 1921, each with Bristol F2b Fighter aeroplanes.

The R.A.F. shared this airfield with a machine-gun platoon of the local 2nd Batt The Border Regiment, to whose commander ( C.M.A. ) they were legally responsible to. In September 1920 this platoon came 2nd in an Army musketry competition that embraced all British Army regiments in Ireland, an indication of this battalion’s overall military capability in Mayo at this time. Other Infantry units of the Border Regiment were stationed in Westport and Ballinrobe.

Maryland House.

Officers from each Squadron were billeted in Maryland House (13) . This was less than a mile from the Airfield and conveniently close to the Town’s railway station. The house had 7 bedrooms and was situated on 28 acres of land. In 1917 Maryland was rented by the R.F.C. from the estate of Sir Malachy Kelly ( 1850-1916 ), a former Crown Solicitor for Mayo and later Chief Crown Solicitor for Ireland. He had offices in Ellison St. Castlebar where Ernie O Malley’s father, Luke, was Managing Clerk. Malachy Kelly was a staunch Unionist in outlook and was knighted in 1912. Countess Markievicz once wrote that Malachy Kelly boasted he could ‘ swing ‘ any jury in Ireland. He died on March 25th 1916 and his funeral was one of the largest seen in the then resolutely Unionist town of Castlebar (14).

Ground support personnel to the RFC/RAF squadrons lived in wooden huts and tents beside the airfield. Both personnel and machines were constantly subject to the inclement West of Ireland weather, on one occasion experiencing severe damage to aircraft in a winter storm.

Activities of the RFC/RAF.

Initially the Squadrons role in Castlebar was that of a training and transport type as well as aerial anti-submarine reconnaissance along the West coast. During WW1 British naval intelligence was fearful that German submarines were getting supplies of fresh food, water and fuel from local Sinn Fein sympathisers in bays along the coast as apparently occurred on a beach near Rosport in North Mayo (15a). Michael Henry in his BMH witness statement also mentions fuel being conveyed by local Volunteers to the townland of Carrateigue in North West Mayo and of arms being landed. He himself possessed a German Parabellum that came from a German submarine.

Such aerial duties were not without their share of accidents locally at Castlebar with the loss of five aeroplanes and three fatalities : a 2nd Lieutenant Fred Clarke, age 24, who died from injuries on 6th June 1919 in an aeroplane accident and a Major Henry Francis Chad M.C. from the 2nd Battalion, The Border Regiment, who is buried in the Church of Ireland cemetery in Mountain View ,( formerly Church St. ) Castlebar. Major Chads had been flown to Dublin from Castlebar to give evidence against The Freemans Journal over an incident at Turlough Village involving a military lorry. On their return on the 28th August 1920, the plane, a Bristol F2B ( F4528) piloted by Pilot Officer Norman Herford Dimmock hit a trestle at the end of the airfield killing Major Chads and seriously injuring the pilot. The funeral cortege to the Church of Ireland cemetery in MountainView, Castlebar, was impressive . Soldiers lined the route in double-file while two Army bands took part. Business premises in Castlebar Town were compelled to close for the event as reported by the Connaught Telegraph 4 September 1920 thereby inadvertently allowing the townspeople to attend a Cycling and Sports Meeting in the grounds of the local Mayo Asylum which the Mayo Brigade used for a covert meeting in which the Mayo Brigade was reorganised into four brigade areas, North, South, East and West. The third fatality involved a 17 year old soldier, Pvte. Heap, from The Border Regiment who was shot dead by his friend Pvte. Partington on the 29th December 1920 as part of a prank while the latter was on sentry duty.

In general, the relationship between the R.F.C. and the local people was good initially. Shortly after their arrival they held an air display in the local Airfield on 17 August 1918, watched by a large crowd. They acquired dairy products from local farmers for the Camp. There were air displays throughout the county and officers were welcomed into the social life of the town. Two R.F.C. members, William Munnelly from Castlebar and James Mee from Mullingar and later resident of Castlebar frequently landed at Castlebar during the 1914-1918 WW1.

Bristol Fighter F4351 at Castlebar.

‘Showing the flag‘.

After the R.A.F. was informed by the R.I.C. that Resident Magistrate John Charles Milling, a native of Westport and a former policeman, had been assassinated in Westport by the IRA on the night of the 29th March 1919 the Commanding Officer of the 2nd Batt, The Border Regiment who was the de facto C.M.A. requested the R.A.F. to make a flyover of Castlebar and Westport ‘ to show the flag ‘ (7ibid). Lieut. Dykes led a flight of five RE8’s from Castlebar over Westport on the day after the killing where they let off bursts of ammunition from the Vickers machine-gun mounted on the port wing as well as from the Lewis gun in the rear observer’s compartment. The Lewis light machine-gun had a circular magazine that held 47 rounds of 0.303 ammunition. In addition, each RE8 biplane had a pair of bomb racks at the wing roots that carried two pairs of 20lb bombs which were duly dropped into the sea off Westport thereby ’showing the flag ‘ as ordered by the C.M.A. Westport was then put under Martial Law nobody getting in or out of of the town for a time. Later, after the Truce was declared, the British Chief Justice and Master of the Rolls gave his opinion that the imposition of Martial Law everywhere in Ireland was itself illegal.

Lieut. Dykes, on advice from London , patrolled along the West coast to welcome the first West to East transatlantic flight of Alcock and Brown on board their modified Vickers-Vimy bomber. On 15 June 1919 he finally spotted their crash-site 4kms south of Clifden at Derrigimlagh ,behind the Marconi Station, whereupon he flew back to Castlebar and advised London by telegraph of Alcock and Brown’s arrival. Castlebar Post Office, like virtually every other town in Connaught at the time, including Galway, did not have a telephone system of its own then though it did possess a telegraph system. The R.I.C., however , did have their own telephone system throughout the country. A British military wireless network was not developed until the end of 1921 by which time the War of Independence was over by six months ( 15b ), while a civilian telephone system West of the Shannon did not exist until 1927, ( and in Castlebar until 1928 ).

For the next year Lieut. Dykes continued to patrol the local countryside with his C-flight of six RE8’s from 105 Squadron at Castlebar, on one occasion on the 17th July 1919 at 9.10 pm, welcoming the Airship R34 as it returned from the US by dipping his wings in salute, as the Airship crossed the Mayo coast and echoing the appearance of a mysterious airship that passed over the town of Newport on Wednesday January 8th 1913 at 6.40 pm, at a height of 500 to 1000 feet, as mentioned in the Irish Times on the 11 January 1913. This event was witnessed by 2 members of the RIC one of whom a Sgt. Padian telegraphed Westport RIC station to look out for it. Poor serviceability of existing aeroplanes was a frequent problem, however, as recorded on one occasion in No.100 Squadron War Diary for 14 March 1921, three contact patrols with infantry in the Ballinrobe area “ rounding up IRA “ ( having to ) be abandoned due to engine trouble. Despite such hiccups, a flight from 100 Squadron at Casrlebar continued to patrol as far as the Athlone area as required under ‘ The Defence of Ireland Scheme October 1918 “ (15c). Likewise, 3 flights from the Curragh patrolled it’s own locality as well as Dublin and ‘ Ulster ‘: the Oranmore flight patrolled the Limerick area while Fermoy was patrolled by it’s two resident flights.

Because of their existing terms of engagement C-Flight out of Castlebar was not able to engage directly with active IRA units until 24 March 1921 but instead reported any observed activity to the Competent Military Authority ( O.C. 2nd Battalion The Border Regiment ) on landing. Two weeks earlier a Sunday supplement to a Milan newspaper La Domenica de Corriere ( 7 March 1921 ) showed British aeroplanes in a fictious attack on the IRA, in a full colour illustration. The caption in Italian read ‘The airmen foil an ambush by rebels on trucks loaded with troops, killing 5 of the assailants‘ . In the propaganda war the Italian Press mostly deferred to British ‘spin‘. Up to then aeroplanes could challenge at will those on the ground as described by Michael Kilroy X as happening to a very young and small girl , Maggie Mc Donnell, who was pursued repeatedly by a low-flying aeroplane as she made her way over a hill to a neighbour’s ( Frank Chambers ) house in Upper Skerdagh after a party of Black and Tans had earlier raided the Mc Donnell home close-by, on 23 May 1921, the day of the Battle of Skerdagh (16).

Air Operations.

After the formation of the four Mayo Brigades ( North, South, East, and West ) in July 1920 greater activity was demanded by G.H.Q. and Michael Collins for action in the West and elsewhere in an attempt to divert British Army men and resources from the South of Ireland where the Volunteers were under severe pressure. In response, in the Spring of 1921, a decision was made by Michael Kilroy, O.C. West Mayo Brigade, to form an active service unit or Flying Column to engage the enemy despite a paucity of weapons (especially ammunition), and a battle-hardened British Army with aerial support, in opposition.

Military activity by the West Mayo Flying Column , however , invariably resulted in an aerial pursuit by the R.A.F. as happened after the Kilmeena and Carrowkennedy Ambushes, where communication with R.A.F. Castlebar was important. For example, John Feehan, a native of Rossow, Newport and Q.M. to the West Connemara Brigade who had been attending the wedding of his O.C. Petie Joe Mc Donnell to Michael Kilroy’s sister Matilda in the parish church in Kilmeena, just four days before the Kilmeena Ambush( 19th May 1921 ) as they made their way back to Connemara after the ambush stated “A plane passed overhead as we stood on the hill of Corveigh ( south of Aughagower) and we had to run for shelter” (17).

After the Skerdagh affray on 23rd May 1921 R.A.F. search planes were summoned early because an RIC Constable Mc Menamin had made his way on horseback to Newport whence contact was made with Castlebar for aerial support unlike after the Carrowkennedy Ambush ( 2 June 1921) from where the RIC had no way of sending for help until well after the ambush was over X. Michael Kilroy in his Witness Statement wrote ” In support of the search for the ASU after the battle of Skerdagh a hugh operation was mounted by the police and military using aeroplanes with carrier pigeons flying around the whole Nephin Range in North Mayo to create awe and consternation among the people (18). This was a wide road-less and tree-less area with inadequate cover for a retreating Column , so described by Michael Henry, ( WS 1732 p.8 ) and with a scattered population for support. After a night march Kilroy was able to penetrate the encircling British cordon and lead the Column to safety.”

Two weeks earlier men from the West Mayo Brigade had marched cross country to support Tom Maguire’s South Mayo Brigade at the Battle of Tourmakeady but returned after scouts had advised that the engagement was over and that the Column was in retreat over the Partry Mountains pursued by Crown forces guided by aeroplanes with Morse telegraphy facilities on board, as described by Ernie O Malley in ‘ Raids and Rallies ‘. Many years later in ‘ Survivors ‘ Tom Maguire wrote ” An aeroplane came in so low it would deafen you, but it passed on ”(19) Later, on p70, Kilroy wrote ” After the Carrowkennedy Ambush the surrounding district was scouted by enemy planes in the morning before any help was permitted to come along to assist the wounded and dying after the battle ” . This was later corroborated by Ernie o Malley again in Raids andRallies p.202 who stated that, after Carrowkennedy, aircraft from Galway and Castlebar assisted the ground forces of Auxilaries and R.I.C. in a search of the entire mountainous area close-by based on information relayed to the pilots via Morse code, by British Army troops on the ground, all to no avail, the whole Column having escaped. Thomas Heavey in his Witness Statement described the follow up as follows ” After Carrowkennedy the Column retreated towards Leenane and the Killary. A gun-boat from Clew Bay fired rounds at Croagh Patrick, the countryside was cordoned off and searched while aircraft circled overhead (20).

Another member of the Flying Column, Tom Kitterick, their erstwhile Q.M. wrote about Carrowkennedy in his Witness Statement ” We decided to make tracks for for a mountain over Towneyard Lake and as we moved along the the side of the mountain we had to keep dodging the plane which kept swooping down in search of us. At nightfall we attempted to reach the peak of the mountain but when we arrived there we saw the searchlights from the destroyers in Killary Bay sweeping the mountains and returned to our Eagle’s Nest of the day before. By now we had been a week without rest (21). Commandant Sean Gibbons described how after Carrowkennedy the British had an aeroplane out (3rdJune) ” which gave the sentries a lot of trouble “. A few days later as the divided Column retreated towards Leenane he noticed a plane directly overhead ” I was sure the pilot or observer had spotted something unusual because one plane kept flying from there ( a wood where they had taken cover ) to where we had left Kilroy, Kitterick and Rushe for practically the whole of the day. We tried several times to get across the road ( and break cover ) but we were unable to do so on account of plane activity (22). Later John Feehan watched the ‘drive ‘ from the safety of the south side of the Killary as he awaited the arrival of Kilroy and others. ” At 6.30 a plane came along and searched all the islands in the Killary and delayed long enough at each to see there were no men there. Then it passed along the slopes of the mountain scanning the area or men and from our lookout on the mountain the O.C. and myself had the rare experience of looking down on a plane in flight and seeing the pilot and observer clearly. The plane left the Bay after 3/4 of an hour and headed over the Mayo Mountains ( and back to Castlebar ) (17ibid). As Richardson stated ” The IRA did not fear destruction from the air so much as detection 6ibid.

General Macready, British Military Commander in Ireland remarked, just as the Truce was called on the 11th July 1921, that he had practically cornered the ‘biggest murder gang’ in the West of Ireland! In reality, despite 3 to 5000 soldiers and R.I.C. involved in this massive ‘drive’ that was organised from Leenane, with searchlight- bearing destroyers in the Killary and with aeroplanes flying overhead continuously, only one Volunteer, Andy Harney, home to see his father was captured and later released.

These examples of the deleterious effect of air reconnaissance subsequent to military action by the West Mayo Brigade Flying Column illustrate the close cooperation that had evolved between British Army ground forces and the R.A.F. in West Mayo as the conflict progressed. One practical example of their mutual support, at a request by the Col. Commandant, Galway Brigade ( British Army ), involved an aeroplane from 100 Squadron at Castlebar on the 26 April 1921 being despatched in a successful search for a delayed armoured-car convoy carrying the British Military Commander in the Midlands and Connaught, Major General Jeudwine, who had been on a tour of inspection of garrisons in the Castlebar-Claremorris area.

While at the start of the War of Independence the R.F.C./R.A.F. was hampered by poor aircraft supply and maintenance, communication difficulties and inadequate cooperation between the Army and R.I.C., by the later stages of the conflict air to ground integration was greatly improved between Army and R.A.F. commanders as well as better wireless communications and better reconnaissance, whether armed, visual or photographic. Not widely acknowledged, these lessons in Ireland were to be further refined by the R.A.F. in subsequent ‘ colonial air policing ‘ actions elsewhere as in Kurdistan, Aden, Iraq and Palestine ( 8ibid). Ultimately the R.A.F. would incorporate these experiences into a written doctrine for their War Manuals in the inter-war years (23).

Michael Brennan O.C. East Clare Brigade later noted that ” The addition of (more) aeroplanes and armoured lorries would have made short work of us “. Good leadership and luck by Michael Kilroy, who was not unaware of the aeroplane menace, saved the West Mayo Flying Column on more than one occasion. With the likelihood of enhanced activity and surveillance by the R.A.F. in the future and also having acquired permission to use their on-board machine-guns and bombs at will, further military action by the I.R.A. was likely to be even more seriously curtailed as the War of Independence continued.

References .

(1) French to Lloyd George , 18 April 1918 MAI BMH CD 178 /1/2

(2) Sheehan , William (2005) , ‘ British Voices from the Irish War of Independence 1918-1921 ’. Cork ( Collins Press), p151 .

(2b) Bond , Brian. 1980. ‘ British Military Policy between the Two World Wars ‘ . Oxford. Clarendon Press. p18.

(3) NAUK WO 141/45, Worthington-Evans memorandum, 29March 1921.

(4) NAUK AIR 5/214, No.2 Squadron War Diary for March 1921.

(5) Townsend, Charles(1975). ‘ The British Campaign in Ireland 1919-1921 ‘ Oxford (OUP) p170.

(6) Richardson, David (2016 ‘The Royal Air Force and the Irish War of Independence 1918-1922‘. Air Power Review Autumn/Winter. Vol.19 No.3.

(7) Dykes, Capt. W. Urquhart. (1999) ‘ Reminiscences 1917-1919 of a Pilot flying with the RFC in 1918 and with the RAF in 1919 in what is now the Irish Republic ‘. p67 1978. (Urquhart-Dykes and Lord ).

(8)Hofman, Bruce. ( Jan 1.1990). ‘ British Air Power in Peripheral Conflict 1916-1976 ‘. Rand Corp. R-3749-Af.

(9)Londen, Pete. (2015). ‘ Airwar over Ireland : Airpower in the Civil War ‘. Aeroplane. Oct. p33-37.

(9b) Macready, Neville. ‘ Annals of an Active Life‘, vol. 2 ( London :Hutchinson n.d. ), p 620.

(9c) Yeates, Padraig. ‘Lockout : Dublin 1913‘.

(10) NAUK AIR 8/22, Churchill to Trenchard 24Sept 1920.

(11) Howley,Thomas. BMH WS 1122.

(12)Cross and Cockade ( 1918 ). ‘ Gazeteer of Flying Sites in the UK and Ireland , Part 4‘.

(13) Marylands, Castlebar, Co. Mayo. Residence of Malachy Kelly. Illustration. ‘The Irish Builder‘. Vol.XLIV, No.1036, p 1568, Jan.25 1903.

(14) Castlebar Nostalgia Boards. (2Dec.2013 ). Posted by Alan King .

(15a) Henry, Michael BMH WS 1732. p3

( 15b ) General Staff 6th Division. ‘ The Irish Rebellion in the 6th Dvsn.Area ; From after the 1916 Rebellion to Dec. 1921 ‘ . Annex v1. Papers of General Sir Patrick Strickland. IWM p363.

(15c ) Philpot Ian M.( 2005 ). ‘ The Royal Air Force ‘ :Vol. 1 The Trenchard Years 1918-1919. Chapter 4 , Air control in the Middle East, India and Ireland. Pen and Sword Books Ltd.

(16) Mayo County Library. Statement by General Michael Kilroy, Newport, Co. Mayo. Part2 . Active Service Operations.

(17) Feehan, John. BMH WS 1692, p73, and p81.

(18)Kilroy, Michael. BMH WS 1162. p56

(19) Mac Eoin, Uinseann. (1980) Tom Maguire. ‘Survivors‘. Argenta Publications p286.

(20) Heavey, Thomas. BMH WS 1668. p59.

(21) Kitterick, Tom. BMH WS 872. p47.

(22) Gibbons, Sean. BMH WS 927. p48.

(23) Richie, Dr. Sebastion (2011). ‘ The R.A.F., Small Wars and Insurgencies in the Middle East 1919-1939 ‘. MOD Monograph.

Thanks to Sean Cadden, Westport for drawing my attention to the Michael Kilroy papers in Mayo County Library.

Photographs courtesy of the late Kay Mc Evilly, Cashel House Hotel where Captn. Dykes was a frequent guest.

www.westportheritage.com

www.westportheritage.com