Click to View

One of the men of the West – Patrick J. Kelly

Fr. Vincent Kelly

I was born in 1895 and lived outside the town of Westport with my parents, brothers, and sisters at Carnaclea. When I reached school-going age, I wished to attend the school in Westport. However, my father, Thomas, had a kinsman Pat Kelly, who was Principal of a school at Cogaula. From my first day at school, this teacher took a special interest in me. Afterwards I found out that he was an old Fenian. His teaching was always based on the very highest national lines. My own father also had a strong national outlook. Later, I was most interested listening to him recalling the days when he was young to some of his own pals.

When I finished school, I went to serve my time at the carpentry trade. In 1914, I joined the Volunteers. I always regarded Joe Ring as a guiding star. He was a member of the Bord of Eireann. I became a member of the American Alliance. The aim of these two societies was to free Ireland. Unfortunately, there were often disagreements, and I often witnessed free fights between the rival parties.

The year 1915 brought me to Leenane to work at carpentry with P.J. McDonnell, better known as Petie Joe McDonnell, who afterwards became a noted I.R.A. leader. He very soon persuaded me to join the I.R.B. I worked for four years there, and during those years we devoted most of our spare time to the movement in one way or another.

On St. Patrick’s Day, 1915, we attended a Hibernian parade in Westport. The O’Rahilly spoke there. All the contingents of Hibernians from the different parish groups passed by the platform and paid no attention to his speech, as the idea of physical force did not appeal to them so soon. Our small contingent from Leenane listened attentively to him. That night some of us met The O’Rahilly at a private meeting. We asked him what the chances were of procuring arms. Pulling a Webley from his pocket, he replied: ‘If you find the money, we will procure the arms.’ He stated that he regretted the fact very much that the others did not listen to him when he spoke. He said that in a year from then they would see things in a different light. His prophecy was all too true. The year 1916 changed the outlook of those young men. Unfortunately, they did not get a chance to hear him speak again, as he was killed in the Insurrection. God rest his soul.

I first met Michael Kilroy when he came to Leenane to visit Pete McDonnell. Both of them were going to attend a Volunteer training camp which was to be held in Clare. I was selected as captain of the Leenane Company. We did some training, target practice – with .22 rifles which Pete had bought for us. One evening, as I was taking the rifle out to Glanagimla, I suddenly observed an R.I.C. man coming round the bend of the road. I slipped the rifle in across the wall, believing that he hadn’t seen the movement as he was still a distance away. My intention was to proceed as if nothing had happened. On second thought, I decided this would be silly, if by any chance I lost the rifle. So I put my foot on the wall and pretended to tie my shoelace. I was really surprised when he jumped off his bike and said: ‘ls that a rifle you slipped across the wall?’ I replied, ‘You had better pass on.’ Luckily, he took my advice.

We did not have any proper guns for rifle practice, so Jack Feehan and I made some rough wooden ones and painted them up nicely. One evening I was taking one of them openly through Leenane as I did not consider it an offence to carry such a harmless weapon. As I was crossing the bridge on the Westport Road, two R.I.C. men in a pub spotted me. Thinking they had a big capture, they hopped on their bikes. One of them passed me, while the other came up behind me. They demanded to see the gun. I passed it to one of them, thinking it would be returned to me. One of them said: ‘I must keep this for further examination.’ Regretting that I had not smashed the weapon, I made a dash to take it from him. The other man grabbed me by the back, and both tried to take myself and the gun. I struggled, and they had to pull me along. Eventually they succeeded in taking the gun from me and let me go free. My pals were sorry they had not been with me to assist me recover the gun. However, they teased me by saying that the R.I.C. thought the wooden gun was more important than I was.

On Easter Sunday, 1916, I was sent to Westport by Pete with a dispatch. This suited me, as I would have the weekend at home with my parents and family. On Easter Monday, all kinds of rumours were about regarding the fighting in Dublin. As the week went by there was no definite news. The following Saturday night I went to the Hibernian Hall to see if I could get any definite news, or if anything could be done. Luckily, I met Tom O’Brien of Moyhastin in the hall, and we were informed that all the leading members of the A.O.H. had been warned by the R.I.C. that if they held any meetings they would be arrested. O’Brien was an I.R.B. man. He asked me if I could get any rifles, and to come out to Carrig Hill the following morning. I went there and was amazed to see all the young men under the command of Joseph MacBride. The majority of them were I.R.B. and some of them had shot guns and some rifles. I was placed in the ranks, and we marched into Westport. I thought it was the intention to capture the local barracks. We marched round the town. The R.I.C. were trotting alongside us taking down names, but we ignored them. Next morning a number of our men were arrested in their beds. I went back to Leenane to continue my work.

Things were rather quiet for a long time as most of the leaders were in prison. In 1917 we organized dances and concerts for the prisoners’ benefit. The threat of conscription brought a little bit of activity. The clergy took up the challenge and spoke from the pulpits advising young men to prepare and fight 1f necessary at home, rather than for the oppressor. At that time, I was contemplating going to America, having received my passage from a sister of mine who was living there. Quite a number of young men went to America in order to avoid being conscripted. When I realized the position I decided against emigrating, as I reckoned it would be cowardly to go. I returned the fare to my sister.

Pete McDonnell had an old forge attached to his workshop. He got some steel and started to make pikes. Jack Feehan and I helped him. Pete also bought some ash planks, and had them sent out to Glanagimla, a village 1½ miles across the hill from Leenane. He paid for all this himself and was never compensated. We could only help him by giving our labour free. We worked all day in the forge, and at night we crossed over the hill to the house where the shafts were being fashioned out of the ash planks. We had a number of fine young men from Glen Letterass – the Wallaces, Joyces, Coynes and Flahertys helping us. We got them handsaws, and they actually sawed the planks to the desired thickness. It was good fun as well, but it was a terror to work in the disused old house. As the soot on all the old timber was falling down, our shirts were not worth washing after working there.

We had a large number of pikes ready in the workshop to be sent to the house on the hill, so that they could be shafted. This particular evening, we had been all day polishing and sharpening them on the grindstone. Pete was away in Galway at a meeting. Michael Joyce was in for the day helping Jack and myself. About 8 o’clock, two R.I.C. men came along, and started a patrol outside the workshop. We were about to break for tea at the time. I assumed they were going to raid the premises as soon as they got reinforcements. Our main problem was to shift the pikes. The R.I.C. men never went far enough out of sight to allow us to sling the pikes across into Michael Gannon’ s field. We decided to chance our luck, and we succeeded in landing two sacks of weapons in the field without being noticed. We then went to our tea and waited for transport. Our next problem was to get the weapons from where we had left them. We asked Maggie McDonnell (afterwards Mrs. Feehan) if she could think of any excuse to go to the workshop, and see if the R.I.C. were still there. She was a courageous girl. ‘Yes’, she said, ‘I will go over for the dog’, which had been tied in the workshop. When she got there, she saw the R.I.C. men had taken up a position with their backs to the workshop door. They moved to allow her pass into the workshop, and she came out with the dog, and went on her way to the local pub, where Mrs Cuffe had her employed as a bar maid. The R.I.C. thought this an opportune time to follow her and get a drink. Needless to remark, she had no great objection; it was just what she had planned. Now our chance had come to have the pikes taken away, and we lost no time in having the mission accomplished.

Padhraig Ó Maille was raided by a large force of R.I.C., and he and his brother, Eamonn beat them off. After that, they were forced to go on the run. We often visited them in their hide-out on the mountain. One night, I was going with a dispatch which Pete gave me to bring to the Ó Maille home at Kilmilkin. He also gave me a .32 revolver and some ammunition. Needless to say, I was thrilled to carry the gun. When I got to the top of the hill at Ashmount, I noticed the shiny caps of two R.I.C. coming along. I left my bike against the wall and hopped inside. When they came in line with me, they halted, the sergeant having noticed my bike. He said to his assistant, ‘There is a bike here, we had better take it.’ They made a move to take it, and as I had it only on loan, and did not wish them to take it, I moved up from behind the wall and confronted them. I raised my gun and dared them leave a hand on it. The first man immediately stepped back and stood for some time having a consultation with the other one. I could not hear what they said. They finally turned and moved off, leaving me alone with my bike.

In the General Election of 1918, Padhraig Ó Maille went as a candidate against William O’Malley, and the latter was a Redmonite (or Irish Party). There was very little difficulty in being successful then as, by this time, all the people had given up adherence to John Redmond. It was arranged that Padhraig (still on the run), should go and cast his vote in the Leenane booth where there were only two R.I.C. men on duty. However, wiser counsel prevailed on him, and he did not go there, as it would only intensify the hunt for him, and make things very difficult.

In 1919, we used to mobilise the Volunteers and do a small bit of drill, dodging the R.I.C. who were intent on getting the names of those who were drilling, or trying to accuse them of some other offence. One Sunday, I was drilling a party of Volunteers just outside where Leenane school now stands, in a quiet part of the road. I saw a lorry load of British soldiers, fully armed, coming around the bend of the road. I had also been warned by my scouts of their approach. I gave my men orders to take cover inside the fence. The soldiers had noticed the scurry as some of my men were slow in getting off the road. The soldiers levelled their guns at us; we kept our heads down and they passed on. I ordered my men out and put them through the same manoeuvre several times, until they all could cross the wall as one unit.

I came to work in Westport in 1919, and very soon was placed in charge of Derry half Company. Tom Burke of Doon was company captain. We organised dances, concerts, raffles, etc., to raise funds. There were collections made for railway men who were on strike. All business premises closed for one day in sympathy with them. There were pickets placed on the roads by the I.R.A. to stop people coming into town. I was in charge of a party on the Ballinrobe-Westport Road, half a mile from Westport. Two R.I.C. men, on bicycles and armed, ran straight into us and raised their hands in surrender. I did not think it advisable to disarm them, so I explained our position and asked them to go back, to which they heartily consented. Later, I reported this incident to Commandant Tom Derrig, who had headquarters in the Town Hall, as I was not certain if I had done the proper thing. He smiled and said, ‘If you had disarmed them, you would probably be court-martialled.’ T.P. Flanagan, who afterwards became Mayo County Surveyor, was at headquarters with Derrig. There was a series of lectures given by an officer from H.Q. named McMahon, in the home of Tom Connor, one mile from Westport on the Castlebar road.

Around the year 1920, I was asked by Tom Derrig if l would go to Louisburgh and organise that area. Pete McDonnell had already asked me to go there to take charge of a workshop he had opened. Taking both propositions into account, I decided to go to Louisburgh.

Tom Ketterick introduced me to Tom Fergus of Mullagh, Andrew Harney of Louisburgh, James Sammon of Carramore, and James McDonnell of Cross. Louisburgh Company had more or less become dormant as some of its more active members had been arrested or gone away. Jack Feehan came along to help me with the workshop; he also gave most valuable assistance in organising the district. After a short time, we had 360 volunteers enrolled. It was then decided to form this company into a battalion. I was asked to take charge. I declined as I would much prefer one of the local officers to take command; also, I was not very anxious to stay long in this particular area. However, on being prevailed upon, I decided to take command for a while at least. Pete kept in touch with us; we always met at weekends, sometimes at my home, or at Jack Feehan’s home in Kilmeena. We attended concerts and dances all-round the country from Newport to Aughagower, our only means of transport being the bike. One Monday morning we came through the town of Newport; Pete had some business with Michael Kilroy in Main Street. Jack went into the shop with him; I remained outside. I was in the act of pumping my bicycle wheel in the archway when the local sergeant came along. He asked me my name, and needless to say I gave a false one. He did not seem satisfied and proceeded to ask various questions. I realised there was not much hope of bluffing him, so I left down my bike, stuck my right hand into my trench coat pocket, and stuck out my thumb, saying ‘I would advise you to leave me alone, and don’t ask any more questions.’ I knew that if he tried to apprehend me I could make enough noise to attract the other two in the shop. However, the sergeant left me in peace. Soon, Pete and Jack came on the scene, and we decided to get out of town quickly. The sergeant had met another R.I.C. man and taken up their position on the bridge, our usual exit from the town. Our only weapon was a .32 revolver, which Pete had. He told us to run for it and he could cover us. However, the R.I.C. men seemed to have got cold feet and did not make any effort to hold us up.

On 1 July 1920, a fair-day in Louisburgh, Jack Feehan and I were working in the workshop until lunchtime, when we decided to take the afternoon off and visit the fair. We had just arrived when we noticed great commotion down the street; some of the volunteers who were there saw us and waved us to come to them. There was a free fight going on between some countrymen who had a few drinks too many taken. I blew my whistle and immediately about eighty volunteers who happened to be at the fair came on the scene on the double. I gave them the order to fall-in, left turn, and just then I noticed another squabble going on up the street. I saw four R.I.C. men hauling a man along to the barracks; he struggled violently, which gave us time to come up in line with them. When the R.I.C. saw the volunteers coming close, they immediately decided to pull the man into an alleyway which led to the back entrance of the barracks. We had to act quickly and intercept them before they got inside the gate. I gave the order to double. We got there just in time, and four of us grabbed the police round the waist and took their revolvers from them. They also released the prisoner, who incidentally was John Sammon from Carramore. The thought flashed into my mind as to whether we should go the whole hog and take possession of the barracks, which was an easy job, as there were only three other policemen there at the time and the front door was open. However, we had no permission from our H.Q. to start operations such as that, but later we regretted that we didn’t take the chance, because from that day all of us who were identified had to go’ on the run’ as a result of this episode. Some of the I.R.A. men were arrested in their beds. The R.I.C. garrison in the barracks was strongly reinforced by men from the other barracks and also by some Black and Tans.

There was a friendly R.I.C. man in the barracks who always tipped us off whenever any arrests were contemplated. They got suspicious of him, and as he was in great danger, he thought it better and safer to resign from the force. We were raided several times at night, but we took the precaution of not sleeping at home. One evening I was alone in the workshop, when a lorry load of ‘Tans’ came from Westport, picked up some R.I.C. men at the local barracks, and made a dash to surround my workshop. Fortunately, I was tipped off by Anthony O’Toole, who had been working in a field nearby and saw the lorry approaching the town. I just succeeded in getting away safely and decided not to go back to work anymore, which decision gave me more time for the organisation.

One day Jack Feehan and I were cycling from Westport, and called to Jim Fair’s house at Glosh, Lecanvey, where we were always welcome. We were just inside the house when a lorry of militia passed by, and we noticed an R.I.C. man named McGovern, who was stationed in Louisburgh, in the lorry, and who could identify us if we were caught. They did not stop at the barracks at Louisburgh but made straight for my workshop. They were disappointed and drew a blank.

Andy Harney, who was battalion adjutant, brought Jack and me to the house of John O’Dowd whom we had not previously met. He, as clerk of the Petty Sessions, was not publicly identified with the movement; he was also an I.R.B. man. He informed us he was going to resign his job as he felt he could not bluff his way any longer. We advised him to hold on a little longer, but he was not convinced. He presented us both with two rifles and one short Webley and told us that he had got them from his cousin, Major John MacBride, some years ago. These were our first rifles, and we thanked him for them. Now for a place to store them. Andy informed us that everything was fixed. He brought us across country about two miles to a farmer’s house, and introduced us to his fiancee, a Miss Fergus. She took our guns and put them under the mattress. Next, she gave us a fine currant cake. I said to Andy ‘I hope the girl I pick will be as loyal.’ He replied, ‘She will indeed, and I know a nice little girl who has a great liking for you; she also comes from very good stock.’

I had met Kathleen O’Reilly some time previously at a dance in Louisburgh, and Andy enjoyed teasing me about her. I was not anxious to get attached to anyone in particular on account of the uncertainty that was prevailing at the time. I went to Leenane on business and was asked by Pete to accompany him on a bodyguard to Padhraig O’Maille, who was going to Dublin to attend a meeting of an Dail. Patrick Joyce of Bayview volunteered to drive us; we went through Cong and Headford; we called at the house of Rev. Fr. Ford in Clarren, where we were graciously received in the early hours of the morning. On our return journey we were held up by a party of men in a motor car. Who did they happen to be but Jack Feehan, Broddie Malone, and Tom Ketterick, with a prisoner who refused to obey a ruling of the Sinn Fein court in Louisburgh and sought protection from the R.I.C. We took the prisoner from them and placed him under house arrest at the home of John Bernard Walshe of Mount Govnagh, Kilmilkin. Next night we got Tommie O’Malley to drive both the prisoner and us to Corofin to a family called Daly who were cousins of Tommie. The volunteers took charge and had him work on that farm, and he was released later when he gave assurance that he would comply with the ruling of the court.

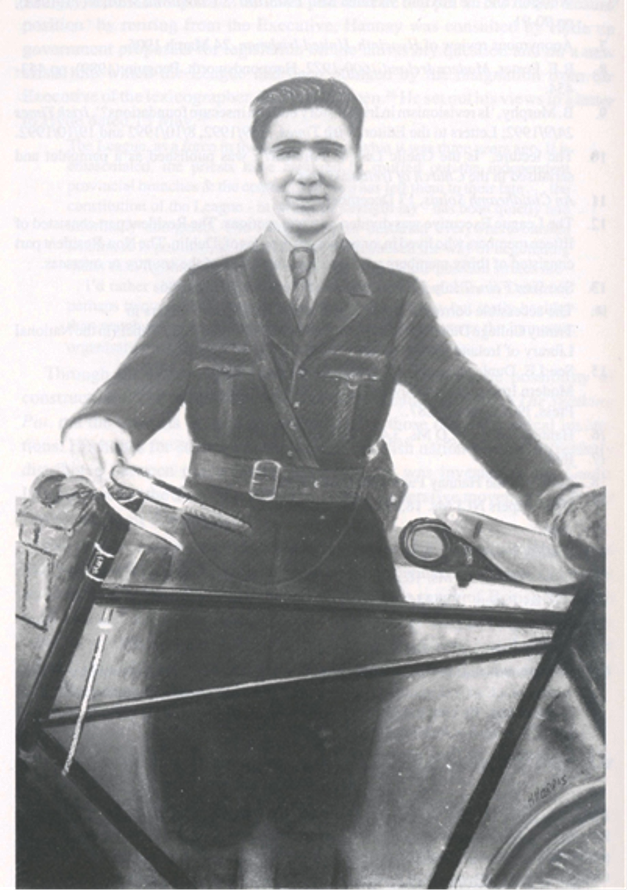

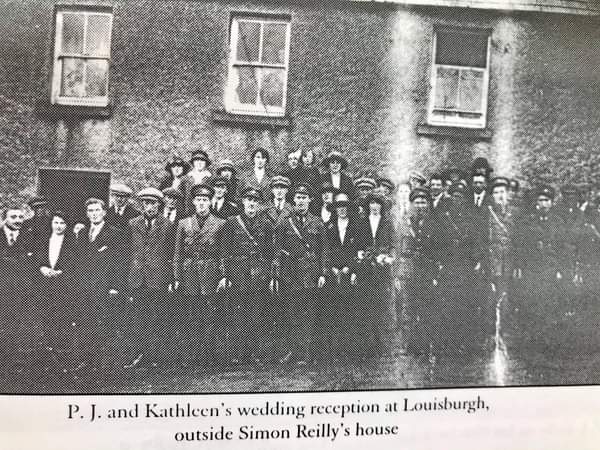

Left: Nancy O’ Malley, bridesmaid (cousin of the bride), Kathleen O’Reilly (bride), P. J. Kelly (groom) and Edward Kelly, (best man), brother of groom.

I came back again to the Louisburgh area and Jack Feehan went to Leenane. I missed him a lot as we were very close friends. Andrew Harney got married to his young bride, and they both started a small shop in the town. She came to us occasionally and brought us supplies. I asked her to bring Kathleen O’Reilly along with her some night, and shortly after that they both arrived at our hide out with supplies. I think that I never felt happier than on that same night meeting Kathleen again. I did not want to admit to myself, much less to her, that I cared very much for her, and I also felt that something had happened to me. I met her several times afterwards by appointment. She is now my wife, and no truer wife or sweetheart ever lived.

We transported the two rifles to Leenane, as Jack said he had a safe place for them. I was called to Leenane one night; it was to arrest some farmer’s son, and search for furniture that had been stolen from Kylemore Castle (now Kylemore Abbey). To my surprise I discovered that Jack’s hiding place for the rifles was the Parish Priest’s house. After the job was finished, we called back to the P.P. and having tapped on his window, we gained admittance to the hospitable Father Cunningham, whose confidence in us helped us enormously.

We had raised money as a result of concerts and dances, and gave it to Tom Ketterick who was brigade Q.M. He sent me a dispatch to come to Westport. I asked Joe Heneghan if he would drive James Sammon and myself to Westport, and he did so. He brought along his cousin, Miss Walshe. We met Tom Ketterick outside the town, and Miss Walshe went into town to visit her sister. Tom brought us to the townland of Owenwee where we met Peter Joyce and his father who was in charge of the dump. They handed us over six Lee Enfield rifles, and two ‘Peter the Painter’ revolvers. Tom loaded the pistols and showed us how to use them, as we expected we might be held up at Belclare, where there usually was an outpost of military. We placed the rifles under the back seat, picked up Miss Walshe, and she never realised the position until we reached Cullen cross roads where we were met by Captain Fergus, 4th Company, to whom we handed over the guns.

I used to go to the Westport area to attend Brigade Councils, etc. Tom Derrig was down with me at my father’s home on a Sunday evening. He left me to go visit his mother who lived on High Street and was arrested next morning by the R.I.C. I called to see Ned Moane at his home next day; he was preparing to leave it as it was not safe to delay any longer. He decided to accompany me to Louisburgh to arrange some lines of communication across the mountains, as we felt we could no longer use the roads in safety. Ned decided to take Tom Heavey, a next-door neighbour, with him. He said to me that it would be a mistake to leave this fine young lad after us, as he would most likely be arrested. Ned arranged for his young wife, who was expecting a baby, to go into the District Hospital, and he went across the hills to Durliss in the Louisburgh area. A week later, Ned was the proud father of a son. He asked Tom Heavey and me to escort him into the hospital to see his wife and baby. This we gladly did. It was indeed pretty risky at the time, as the R.I.C. would have had a welcoming party for us had they got any news of the happy occasion. Ned sent Heavey ahead to scout the approach to the hospital, and soon we got the all-clear signal. Heavey and I waited on guard while Ned visited his wife and baby.

We afterwards attended a Brigade Council meeting which was held at Moyhasten. Michael Kilroy presided. It was decided to form a ‘Flying Column’ and take the field against the enemy as soon as possible. There was much preliminary work to be done. Tom Ketterick and I were to go to Westport for some supplies. He was Brigade Q.M., and I was asked to accompany him, and purchase wire-cutters and tools which might be useful. We decided to go into town the following night. We went to Shanley’s drapery shop and going in we noticed two soldiers outside. Tom warned me to keep my eye on the door while he went to the far end of the shop to attend to his business. I was taken by surprise to hear a revolver shot, and on looking around saw Tom hopping on one leg. I went to help him, and as there was no back exit, we had to come through the front door. By now the two soldiers had fled. I got Tom into a laneway which connected Bridge St. with James’s St. just opposite the R.I.C. Barracks. There was a very friendly family named Conway at the other end of the lane, and with the assistance of John Burke, who had the garage on Bridge St., we brought Tom into Conway’s house. I sent a message to Broddie Malone who got a doctor, and afterwards arranged for a car and a bodyguard to take Tom to a house in the country. What really happened Tom was that, as he was describing some incident to the draper which happened the night previously, Tom had his hand on his automatic on account of the soldiers outside. It went off suddenly and accidentally, and the bullet passed under his kneecap, and out in the side of his shin. After this incident, I went on to Mulloy’s Shop in Shop St., to buy wire cutters, etc. I was chatting to the assistant, John Glynn, when suddenly I recognised an R.I.C. man named McGovern coming in the door. He was the tout who was accompanying the military on their raids on our homes. I did not wish to fall into his hands, so I immediately drew my revolver, and covered him off, at the same time stepping behind a stack of paint tins in the shop. This afforded me ample cover from attack. McGovern turned around quickly and said something to the assistant and went out of the shop. I think it was not for love of me that he did so. I was tapped on the shoulder by the friendly assistant in the shop and led through the private house into the adjoining yard, from where I made my way to the open country. I was informed afterwards that the R.I.C. man said to the assistant, ‘That’s one of the boys, but I did not see him at all.’

This was in the month of October 1920. In the following month the military became very active, raiding day and night in the area. Most of the officers had to go on the run permanently. Some farmers gave them their shotguns voluntarily. We had good fun too raiding the loyalist houses. The occupants barred all doors, so that we had to improvise a battering ram to force the door of some houses. In another house we had to use a ladder to procure entry, when a swift search revealed a gun which we took.

It was decided by the brigade about 1 March to take the field against the enemy. We had planned a long while for this, and after the Brigade O/C M.Kilroy, and vice-O/C Ned Moane, visited the area it was decided that the first blow would be struck in Louisburgh, where twenty of the enemy had the barracks well protected with barbed wire, steel shutters, etc. They had two Crossley tenders in which the ‘Tans’ carried out their nightly raids, bayoneting and ill-treating civilians when their quarry had eluded them. After he had made due reconnaissance and inspection of suitable ambush sites on the Louisburgh Westport road, for the position of riflemen to intercept the enemy from Westport while the attack was in progress, Michael Kilroy looked down from the hill overlooking the town and said, ‘Louisburgh, fare thee well for the moment, ’till we come again to bring thee freedom.’ A week later, Kilroy and about thirty men arrived in Culleen and went to Michael O’Malley’s house where they were always welcome. Our unit mobilised in Tully Lodge, kindly given us by the owner, John O’Dowd, himself being sent into Westport to carry out intelligence work. I being the battalion commander, crossed from one camp to another two or three times that day riding a horse. That was 16 March 1921.

At a Council of officers, taking all the factors into account, Brigadier Kilroy decided instead to move the men to an ambush point at Glosh near Lecanvey. He instructed me to take four or five men along and go into Louisburgh and to shoot two Black & Tans who were paying nightly visits to supporters of ours and threatening them. Having gone in on three successive nights, we failed to make contact, as the police were aware of armed men in the district and consequently kept to barracks. On the third night however, Martin O’Reilly and John P. Harney, who had previously scouted the town, observed two ‘Tans’ enter a pub in Bridge St. and reported to the officers waiting at the bridge at the end of the street. Immediately Joe Baker and I hurried up to the place indicated, where the ‘Tans’ had entered, and when halfway up the street we saw two figures leaving the same pub. Notwithstanding, we hastened our pace, while the ‘Tans’ ran for cover and dived into the barracks before we could get a shot at them. In addition, we placed the following men at strategic points at the entrance to the town: Andy Harney, the late Seamus MacEvilly (killed in combat at Kilmeena May 1921) and Jim Harney.

Michael Kilroy and his men remained all night in an ambush position in Glosh, and had only withdrawn at dawn when a lorry load of ‘Tans’ proceeded along the road to Louisburgh. The column rushed down to their positions and waited there all day for the ‘Tans’ to return. However, they waited in vain. Obviously, they had been tipped off, and they returned via the Leenane-Westport road. On 21 March, on receipt of a dispatch from Kilroy, myself, Joe Baker, Seamus MacEvilly, Andrew Harney, James Harney, and Tom Fergus, crossed over Loughta Mountain and were met by two guides – Peter McLaughlin, Oughty, and another man. They were instructed to bring us to the Drummin Barracks. Verey lights were sent up from the same. We failed to contact the brigade A.S.U. as it had withdrawn after the encounter with four R.I.C. at Derrykillew that evening, where two of the enemy were killed.

Once again, we returned to the Louisburgh area on 22 March and arranged to go in that night to the town, as we were anxious to get something done in that area before joining up with the brigade A.S.U. again. Unfortunately, a revolver was discharged accidentally, the bullet passing through Andy Harney’ s stomach and lodging in my arm. Doctor O’Grady was sent for and came at once. He dressed the wounds and made us comfortable. A week or so afterwards, on receipt of a dispatch from the brigade, Joe Baker and S. MacEvilly left to join up with the brigade. We sent two extra rifles with them, being unable to travel ourselves. This was the last time we saw Seamus.

At the end of April, a party of Volunteers under· Captain D. Sammon was billeted in an untenanted house in the village of Askelane, two miles from Louisburgh. They were suddenly surprised by a party of ‘Tans’ who opened fire on them at close range. Only scant cover was available, and the men being unarmed except for two revolvers, returned the fire while the bullets of the enemy pierced the ground around them. Three of the party were captured, one being slightly wounded; the other two escaped. Those who took part in this skirmish were Dan Sammon, Pat McNamara, James Sammon, Tom Sammon, Joseph Fergus, and John Sammon. One of the volunteers died and was buried in Kilgeever. Andy Harney and I crossed the Kilgeever hill, and when the grave was just closed, we walked over and fired three revolver shots. We could not delay as it was in sight of the barracks.

Next Sunday, I made an appointment to meet Kathleen and I expected I would soon be leaving the area to join the brigade A.S.U. It was a nice sunny day, and she cycled out to the crossroads at Kilgeever. We were sitting on the fence facing the road, which was only about 100 yards away. We saw about twelve R.I.C. coming along the road which was parallel to the fence. I realised that it would be fatal for us to move as we were on the wrong side of the fence. I had two revolvers at the ready. Kathleen asked me to let her have one. I knew they would not come across the open field to where we were, but there was a branch road which came up on our left almost ten yards away. I decided not to open fire if they did not turn that way. They passed on however, and we both felt so relieved. She was a great girl. I kissed her goodbye, thinking to myself I might never see her again, but I vowed inwardly that if I did, when we had our freedom, I would tell her that there was no other girl but her for me in the world.

I had Tom Fergus and Jim Harney with me as a bodyguard. They had our position covered. We went that evening and collected Captain Dan Sammon and Pat McNamara and decided we would make it unpleasant for those gents to take exercise. I was informed by our intelligence that the enemy did short patrols around the town (a mile or so distant), taking different routes on each occasion. I decided the only way to contact them was by billeting in houses adjacent to the town, namely William Ward’s, Mooneen; Owen O’Malley’s, Coolacoon; John MacEvilly’s of Bunowen; and John O’Malley’s of Cahir. When staying in Owen O’Malley’s, we observed R.I.C. coming in our direction. We took up position and watched for them, and again were doomed to disappointment when they gave us the slip.

At the end of May I received a dispatch from O/C Brigade to link up with the brigade unit. We decided to make a call on the Harney family at Tooreen. On approaching the house, we observed a patrol of ‘Tans’ proceeding along the road to Kilgeever. We took up positions to intercept them on their return. We discovered afterwards that they took a short cut across the fields, returning to the barracks. We continued that night on our journey and reached the village of Owenwee, leaving Andrew Harney, who was not fully recovered from his wound, in charge of communications. On arrival, Peter Joyce informed us that the Brigade unit had moved off to Claddy, having left word for us to follow them. We arrived there a few hours later. This was the morning of 2 June 1921, on which the famous Carrowkennedy ambush took place.

We met Brigadier Kilroy and his column and told him we had been travelling all night. He told us to go and have a sleep in one of the houses in which they were staying. We were not long in bed when we were told three lorry loads of military had gone towards Leenane, and the column was preparing to attack them on their return journey. We immediately jumped out of bed, dressed and soon caught up with the column, which was already on its way across the fields, led by Broddie Malone. I caught up with Kilroy and Joe Ring, who had travelled down the boreen. Michael said to me, I’m sorry Paddy you had not a longer rest, but I am sure you would not wish to miss this opportunity of getting some more much needed rifles and ammunition. ‘He then outlined his plans to me briefly, positions to be taken etc. He instructed me thus, ‘You take your four men to the rock you see in the centre of the bog.’ This clump of rock stood about 500 yards away from the No. 1 and No. 2 positions, and had a command of the Leenane Road for about half a mile or so. He said he would open fire first. The reason he placed me in that position was, in case one of the lorries would be a long distance behind, or there might just be reinforcements coming that way. I did not like the idea of going away so far from the main body, but an order is an order. We were only half-way across the bog going in the direction of the large clump of rock, when we got a signal from No. 2 that the enemy was approaching. We dropped down flat in the bog and let the lorries pass. When two of the lorries had rounded the bend out of our sight fire was opened. We had just time to get a volley into the third before it got out of sight. We then proceeded to the clump of rock and kept vigil. The operation started about 3 p.m. and continued till sunset, when the R.I.C. surrendered 23 rifles, 25 revolvers, l Lewis gun, 60 Mills bombs, and 5,000 rounds of ammo. Three lorries were burned. The column mobilised in Claddy where we had some well-earned refreshments, and afterwards we went to Drummin and arrived at Moumacasser at daylight. We observed an aeroplane scouting the position at Carrowkennedy and not till it signalled all clear did the enemy forces venture into that area.

Next day the Brigade unit arrived in E/Co. area Cullen – there they rested and enjoyed the hospitality of local people such as Edward Kelly’s, Red Pat Joyce of Durless, Black Pat Joyce, Brian Scahill of Culeen and Tom Fergus. These staunch freedom-loving nationalist homes sheltered and fed us for two days after the victorious battle of Carrowkennedy. Captain Tom Fergus and Andy Harney took turns in charge of outposts, sending local men wearing bawneens and with dog and stick (pretending to be looking for sheep) to locate any possible enemy movement. Soon the unit moved on to the village of Cregganbawn, nine miles across country, where they were well received by the O’Gradys, J. Tiernan, J. Kilcoyne, Wallaces and others. The next stop was Killeen where Captain T. McGuire was not slow to provide billets and outposts, as this area was bad for strategic reasons, as this portion of country was bounded by Clew Bay and Killary Harbour, leaving only one way out towards the east in the event of a raid. But owing to the very efficient intelligence service from the battalion centre Louisburgh (which was also the enemy stronghold), the chain of scouts, Cumann na mBan and volunteers in charge of John P. Harney and Martin O’Reilly, who were in close touch with the column, ensured their safety. It was decided, nonetheless, not to wait too long, so the next move was to the rugged though picturesque area of Glendavock near Drummin. Commdt. Pete McDonnell paid us a visit while here, accompanied by one of the Wallace brothers of the famed West Mayo Connemara column. We were glad to get such a first-hand account from them of their successful activities against the enemy in their area. Next day we were on the move again – leaving the Louisburgh battalion area, we marched to the Erriff Valley and on to Aughagower. Shraheen company was at this time in the South Mayo brigade area.

After resting for one night, we crossed through the parish of Killawalla, Islandeady, and rested in the village of Ballinacorriga, where I was so pleased to meet many of my old school going pals. I asked for permission of Brigade 0/C to pay a visit to my home which was only two miles away. He granted my request gladly and warned me to be careful, telling me when he next intended to move in case of any mishap. My dear Father and Mother welcomed me as did my brothers and sisters, and I met many kind neighbours.

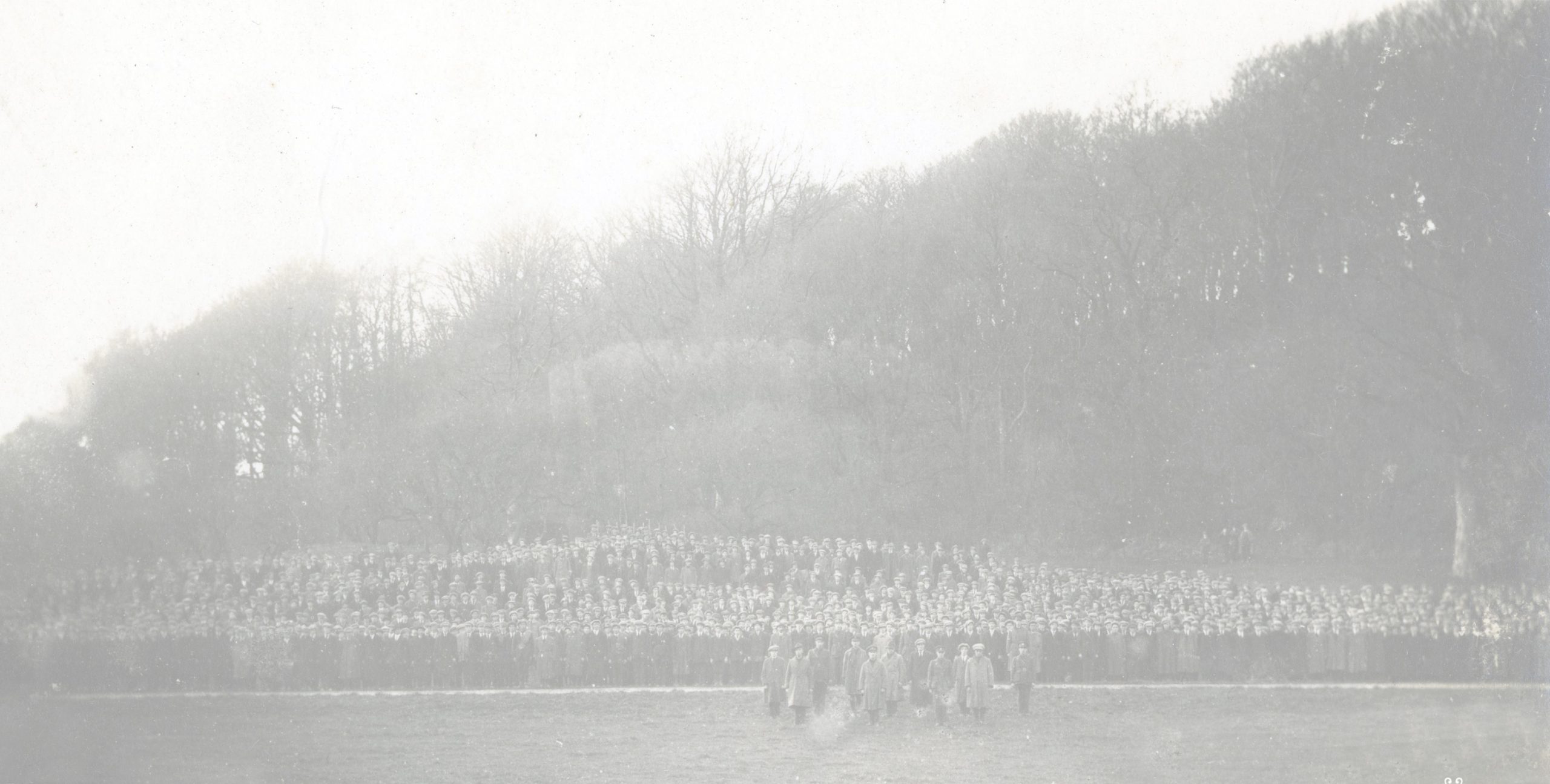

On returning to the column, we moved on to Glenlaur in the Newport area, and on through Derryloughan. We spent the 20th of June in Coolnabinne, and the following day in Derrymartin at the foot of Mount Nephin, where the now famous column picture was taken by Jack Leonard of Lahardaun. The picture which was taken on the southern slopes of Mount Nephin on June 21st at 11.45 p.m. had no light but that of heaven. This picture included all the men who took part in the Carrowkennedy Ambush days earlier, with the exception of Paddy Duffy, Joe Baker and John Berry who were on sentry duty while it was being taken.

Next, we moved to Shanvalley, a little village at the top of Bearnagaoithe (The Windy Gap). We passed through the Windy Gap the following night into Crimlin, thereby following in the footsteps of General Humbert and his French army of 1798. Captain Staunton of the Crimlin Company was responsible for security, while the column were resting next day. We there observed a force of military proceeding along the road towards the village. We took up positions but when they came within a half mile from us, they turned right about and went back towards Crimlin.

We got information that strong forces of military had arrived in Castlebar, and we decided to move further towards the mountains, to the villages of Largan and Gort. Apparently, the military had information also as to our movements, and we had hardly retired to our beds at about 3 a.m. when our sentries spotted the enemy movements. We had barely time to get out, as some men were ill and had to be helped along. Four of us who were billeted in one house, and were getting out as fast as possible, pulling up our socks and strapping on our equipment, when we met our column comrade Michael Kilroy, in full battle array at the back of the garden fence. Apparently, he had not turned in at all that night, having anticipated this round-up by the enemy. He directed the other three men, i.e. Dan Sammon, Pat McNamara, and Jim Harney, to join the rest of the men who were taking up a position on the hill and he asked me to remain with him. We both took up a position where we could plainly observe the movements of the military raiding the houses below. He warned me not to open fire unless they came right up to us. I admired him for his concern for his men and for his bravery, as he insisted on waiting until he got word from above that all the men had taken up their positions, with the exception of two, Paddy Duffy and William Joyce, who were billeted in an isolated house and had not been called. Every house in the townland of Crimlin, Gort, Lurgan, and Greenauns, were searched with the exception of Rowlands, where Duffy and Joyce slept peacefully. They later joined the column in the defence position at 10 a.m. As far as I can remember, this was 23 June, the longest day of the year. Personally, I found it the longest day of my life as we had to wait until darkness to fall before we could move from our position. The military had camped all round us in preparation for a final comb-out of the area on the next day. All the young men in the district were rounded up and put through the third degree, in order to extract information about our plans, but all to no avail, as the people were 100% loyal to our cause, and would gladly have surrendered their lives rather than inform on us. They sent us much-needed food as soon as it was safe to do so. When darkness fell, we again slipped through the lines and after a long march we arrived in the townland of Shunnagh and Parke Coy. was responsible for our security.

We again left our Brigade area and moved to Carracastle, near Bohola, where two days were spent and a very enjoyable dance was arranged by the boys and girls in the area. Military movements were again reported near us, and word was received that the Shunnagh district in which we had spent the night before was thoroughly searched. From Carracastle we proceeded to Prison near Balla, where another dance was arranged for us at the village hall. Carracastle was surrounded that same day. Back again to West Mayo, spending a night in Cloonshunnagh, between Belcarra and Ballyheane. Errew monastery was visited by many of the A.S.U., while the Ballyheane Coy. gave adequate protection. Next move was to Devlish in the Killawalla Coy. area. Here again word was received that strong forces of military were closing in behind-always searching a day behind us.

On the night of Saturday 2 July, the column was billeted in Tonlagee near Aughagower. Information came through L. Sheridan that a military camp was being established in Killawalla, a few miles away. We at once went to Lanmore where further information was given to us of a huge trap closing in around us. Another military camp was being set up at Ballydonlon, about two miles away.

We moved in the grey dawn to Owenwee, where the column had been twenty nine days before, two days before Carrowkennedy. All day Sunday was spent in Owenwee, with every man on the alert. The O/C called all the men together that night and explained the serious situation to them. It was impossible for them (forty men) to engage a highly armed and trained force of about 4,000. Accordingly, the column was to disband into twos and threes and so infiltrate through enemy lines. The column disbanded, and from dawn on Monday 4 July, every house and village in the Westport-Louisburgh area was combed out by the forces of the enemy. This type of pressure was kept up for a number of days, but not one of the wanted men was captured.

The adventures and hairbreadth escapes of the different groups who left Owen wee on that night are well worth recording. Four of us, with five men from Newport, headed west for our own battalion area. We were once more welcomed by the Culleen people, the Hynes, Gavins, Foys, O’Malleys, Kellys, Joyces and Ryders. Old Tom Ryder and his wife and their neighbour, Tom Fergus, and his sister (Mrs Harney) were exceptionally loyal and hospitable. We were only a half-hour in our beds when we were aroused by a volunteer, named Gavin from Lecanvey, who told us that thousands of troops and ‘Tans’ had gone to Louisburgh. We left the house at once and went up on the crest of a hill, where we could observe the enemy movements, and where good cover was available in the deep ravines, cut by the torrents from the Holy Mountain of St. Patrick. An aeroplane scouting came right across over us and searched low over the ravine as if it had spotted someone. This was for us an anxious moment, but luckily the ‘plane continued on its flight and left us in peace.

There was a Land Commission Ganger named Pat Maguire working Glan farm. We asked him to release his men, most of whom were volunteers, and send them to the hills, pretending that they were after sheep. In this way, we were aware of how the roundup was proceeding. We were informed by one of the volunteers who had been in Louisburgh, that Andrew Harney, and his brothers John P. and Larry, were arrested at dawn when they were sleeping in an unoccupied house in Legan farm, near their own father’s house. A large number of young men also were rounded-up that day by the military, who had a camp at Old Head. We then decided, if we could succeed in getting into the area which had been combed-out, we would stand a better than average chance of escaping the net. So, when night fell, we made straight in that direction. It was difficult, as searchlights were being thrown in from gunboats in Clew Bay at intervals of every ten minutes. We reached Mooneen, and then to Tooreen, where we called on the Harney family, who were very upset by the arrests. We decided, however, not to wait, as it was possible that the enemy might just return. We called on Doctor O’Grady, a friend of ours, and who was not suspected by the enemy. We were well received and slept there in a comfortable bed, awakening at intervals because of the rumble of enemy lorries passing outside on the following day.

It was now 9 July. Our reliable Intelligence Officer, Martin O’Reilly, soon made contact with us and advised as to our next move. He suggested his own father’s house as it had been raided that same day and being in the town at the end of Chapel Street it would not be considered a place where we would dare visit. The way was previously scouted by Martin’s sister, Kathleen, and by Miss Julia Harney, now Mrs Con Ryan, both being members of Cumann na mBan. We were duly welcomed by Simon O’Reilly, an old fenian, and his wife, who put us completely at our ease.

Next day, by the arrangement of two mirrors, we could observe the movements of the military and the ‘Tans’ on the street and near the barracks. Next night, 10 July, we moved at 12 noon to O’Malley’s of Cahir, the childhood home of Simon’s wife Bridget O’Malley. On the following day, 11 July, a Truce was declared, and we emerged into the daylight of freedom, and were once more free to walk up the main street of the town, dressed in leggings and riding-breeches, and wearing hobnailed boots, to be welcomed by a host of friends.

Note: The foregoing story was told to and recorded faithfully by Mr Kelly’s son Vincent. It is dedicated to the memory of both Patrick Joseph Kelly and his wife Kathleen (nee O’Reilly).

(This article was first published in the Cathair na Mart journal, vol 12, 1992)

www.westportheritage.com

www.westportheritage.com